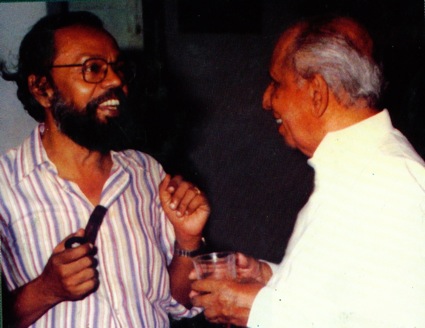

AJ Gunawardana and Lester James Peiris

September 2008 marks 10 years since the sudden death of Dr Ariyasena Jayasekera (A J) Gunawardana, an outstanding university teacher, writer/journalist, cinema personality and art critic. When he failed to regain consciousness from open heart surgery, at the relatively young age of 65, we lost a rare intellectual who had his feet firmly on the ground, and constantly built bridges linking media, culture and society.

AJ’s academic and professional accomplishments are well known and remembered. Having started as a journalist with Daily News, where he was a noted arts and culture correspondent in the 1960s, he went on to obtain a doctorate in performing arts from New York University. Upon return, he pursued a career in academia as a professor of English at the Vidyodaya University (later University of Sri Jayawardenapura) and was closely associated with film and media education. He chaired a Presidential Committee of Inquiry on the Sri Lankan film industry, which issued its report in 1985. In the arts world, he is perhaps best remembered for the screenplays he wrote for three films by Lester James Peries: Baddegama (1980), Kaliyugaya (1982) and Yuganthaya (1985). At the time of his death in September 1998, AJ was working on a biography of the doyen of the Sri Lankan cinema, which was posthumously published in 2005.

AJ’s contributions as opinion writer and columnist have not been as widely acknowledged. AJ was a rare public intellectual who — in his writing and public speaking — stood for a united and multicultural Sri Lankan society. In doing so, he stood apart from many fellow members in the academia and media, his twin fraternities, whose parochialism and misplaced nationalism have propelled us into the current depths of despair. As Sir Arthur C Clarke, a long time friend and associate of AJ, remarked in a poignant tribute: “AJ’s sudden death is a setback in our collective struggles against fanaticism and fundamentalism.”

Moderates are hard to find in any society even in peacetime, and especially rare and endangered in times of conflict. AJ was one such man, but at the same time, he held firm opinions and had the courage of his conviction to express them. He articulated his (often dissenting) views brilliantly, which made him one of the finest commentary writers in our English language press, where he wrote a regular media and culture column for over a decade in the 1980s and 1990s.

AJ was highly multi-disciplinary, had wonderful sense of humour and was totally devoid of pomposity. At a time when artistes and intellectuals assume extremist positions to draw cheap popularity or build larger-than-life images, AJ never used his media platform to oversell a personal agenda. He belonged to that diminishing tribe that still assigns more importance to the song than the singer; hence his use of the pseudonym Jayadeva.

My association with him was in the last decade of his life. Although we shared the same surname (spelt differently!), we were not related, and I never had the opportunity of being his student. His junior by a generation, I related to the genial professor as a fellow writer and occasional partner in mischief in the domains of media and popular culture.

Not so marginal comments

For several years, his and my writing used to appear in every Thursday in The Island (then Sri Lanka’s only independent English daily, and before it was run over by Sinhala nationalists). Often, his Marginal Comments column would be on the leader page, while the weekly science page I compiled and edited was printed on the reverse.

I admired AJ for his column long before I developed a personal acquaintance. Its intentional misnomer was characteristic of the writer. Marginal Comments carried some profound reflections on the larger cultural and societal realities and idiosyncrasies of the time. His depth of understanding and breadth of topics were distinctive, if not unique, in Sri Lankan journalism. Only parallel I can think of is another colleague Ajith Samaranayake, who left us even more prematurely — and just as abruptly — a couple of years ago.

AJ’s weekly column was written during a period that saw many dramatic and sometimes frightening developments in Sri Lankan politics, economy, culture and social life. Economic liberalisation policies introduced in 1977 were now manifesting their social and cultural impacts. The twin genies of Sinhala and Tamil ultra-nationalism were already unleashed, and slowly tightening their ruthless grip over an unsuspecting people. After decades of complete monopoly, the state had finally begun to allow private participation in broadcast media.

This was also the time when intolerance in our society reached such alarming levels that expressing strong opinions on any subject could bring serious personal repercussions — ranging from loss of job to loss of life (sadly, things have only become worse since). Conveniently hiding behind this reality, most intellectuals confined their opinions to the cocktail circuit or university lecture rooms. The betel-chewing, pipe-smoking A J Gunawardana begged to differ — and expressed his views without fear or favour.

His comments spanned a broad scope; the man was unpigeonholeable. This again is a rare phenomenon. On the one hand, we have specialists in the arts, culture and humanities writing about their fields of expertise with varying degrees of candour, compassion and erudition. On the other hand, there are a few with science and technical backgrounds attempting to comment — often not too eloquently — on the social and cultural impacts of developments in their own fields.

Straddling two cultures

AJ, in contrast, demonstrated a strong grasp of both the arts and sciences (thus straddling the ‘two cultures’). Having been exposed to the best of both eastern and western traditions, he also had no insularity or inferiority complexes that pervade our academia.

His column covered a stunning array of sectors, fields and subjects in an authoritative yet readable style. He discussed with authority on the music of Amaradeva, Sri Lankan writing in English, new trends in Sinhala drama, the myth of an ‘Asian cinema’, and the implications of satellite television and the Internet — the favourite ‘whipping boys’ of our self-appointed guardians of ‘culture’. AJ dealt with these and many other topics with the right mix of personalised commentary and dispassionate analysis.

His wide reading was accompanied by abundant empathy and, where warranted, sympathy. He never used his column to demolish individuals or institutions holding different points of view; neither did he turn columns into crass displays of his erudition. To quote from Arthur Clarke’s tribute again:

“He replaced the intellectual arrogance of academia with a healthy scepticism, deep-rooted humanism and a fine sense of humour: in his writing and public speaking, he would query, reflect or ridicule without being devastating.”

One area which interested him a great deal, and formed the basis of many columns, was the many faces of popular culture. Most senior academics would hesitate to probe into such a nebulous and quirky subject, but AJ excelled in this respect. He reflected with equal dexterity on H R Jothipala’s songs, Sri Lanka’s street theatre, the latest box office hits from Bollywood and Hollywood, our near-religious obsession with the game of cricket, and the enduring appeal of political cartoonists from Collette to Wijesoma.

For sure, AJ was not the only one to take up these topics. Occasionally, a sociologist might study a trend with clinical detachment and produce a jargon-heavy research paper. Or a journalist would write a purely descriptive article without much analysis. In contrast, AJ could bring life to any topic he picked, no matter how esoteric it might seem at first glance. He chronicled and commented on established and emerging social and cultural phenomena, sometimes with his tongue firmly in his cheek.

Cartoon universe

One such aspect of pop culture brought us closer together: the syndicated newspaper comic strip called Calvin and Hobbes. Sometime in the early 1990s, we discovered that we were both ardent fans of American cartoonist Bill Watterson’s enduring creation of a six year old boy (Calvin) and his daily adventures with stuffed toy tiger (Hobbes).

In fact, it was AJ’s reflections that heightened my interest in the characters that appeared everyday in The Island at the time. AJ and I saw Watterson engaging in witty and perceptive social commentary through the seemingly mundane and outrageous misdemeanours of Calvin — an over-imaginative child living in a media-saturated (American) society. The comic strip reinforced our belief that good cartoonists are not just good entertainers and social satirists, but also mass philosophers of our time.

For us, Calvin and Hobbes was the first thing we turned to in each day’s issue of The Island; the real world would hit us a minute or two later. On my travels, I used to pick up the latest book collections of Calvin and Hobbes, and pass on to AJ the most interesting extracts. He commented on some in his column; I know he enjoyed all.

And when Watterson — for a complex set of personal and professional reasons — decided on 31 December 1995 to stop drawing the popular comic, we were both devastated. AJ reproduced parts of a letter I wrote, expressing dismay over this calamity. After Calvin and Hobbes, our private universes were never quite the same again. There were reruns, of course, but no more original C&H. Every now and then, AJ would ask me whether I’d heard anything about Watterson changing his mind. Alas, I bore no such good news. (More than 13 years since, Watterson has stuck to his resolve.)

His fascination with Calvin and Hobbes indicated AJ’s child-like interest and curiosity in the widest possible range of human endeavours. These qualities were unaffected by the high positions he held in academia and public life. He was a rare public intellectual for whom nothing was too mundane, and nothing was too sophisticated. Just as Calvin was a constant misfit in his conformist (read: boring) primary school, AJ too was in some ways a ‘misfit’ in the citadels of mediocrity that our institutions of higher learning have become. Long live the misfits — we need plenty more of them!

Public broadcasting

It was only after I moved away from deadline journalism in the mid 1990s that I started interacting more closely with AJ. He advised and partnered with me in endeavours ranging from organising a South Asian documentary film festival in Colombo to catalysing debate on a new vision for public service broadcasting.

He lamented that the tradition of public broadcasting in Sri Lanka had been hijacked by political parties in office to serve their narrow propaganda needs. In a commentary written to the Lanka Guardian only a few weeks before his death, he argued against the then prevailing annual license fee to own radio and television receivers, which was generating millions for SLBC, Rupavahini and ITN. He claimed that our rights as consumers were being grossly violated; we were paying for a product that wasn’t being delivered. (Shortly afterwards, the TV and radio license fee was abolished by the then PA government. In one fell sweep, that removed a key legal argument against the political abuse of state media…was that intentional?)

During the 10 years since his departure, I have often wished we had the benefit of his insight — and foresight — to help navigate through the often bewildering developments in mass media and popular culture, such as the blogging, social networking online, mobile phones and reality television. I can just imagine how he would have ridiculed the recent crude attempts at cultural policing, media censorship and the highly misplaced ‘patriotism’ now popular among certain academics and artistes.

I keep hoping that AJ’s original Marginal Comments would one day be compiled into a book. Years after they were published, many can still be useful rough guides to those of us who struggle to make sense of our topsy-turvy times and our hopelessly mixed-up and globalised world.

Nalaka Gunawardene blogs on media, culture and society at http://movingimages.wordpress.com, and lives in the hope that Bill Watterson would one day come out of retirement…